https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Jimmie-Foxx/

researched and compiled by Carrie Birdsong

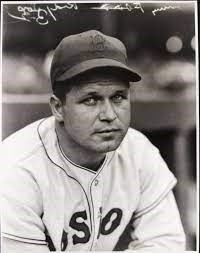

As he had done many times in recent years, Jimmie Foxx

chose to spend the afternoon of July 21, 1967, with his younger brother,

Sam. The two men lived close by one

another in Miami, and often got together to reminisce about the elder Foxx’s

legendary career, in which he slugged 534 home runs, won three MVP awards, and

was elected into the Hall of Fame.

Foxx’s second wife, Dorothy, had passed away in 1966 and his family saw

him becoming lonelier and more depressed.

More and more, the time with his brother seemed to be the only thing to

bring a smile to a man renowned for his generosity and good nature.

As he had done many times in recent years, Jimmie Foxx

chose to spend the afternoon of July 21, 1967, with his younger brother,

Sam. The two men lived close by one

another in Miami, and often got together to reminisce about the elder Foxx’s

legendary career, in which he slugged 534 home runs, won three MVP awards, and

was elected into the Hall of Fame.

Foxx’s second wife, Dorothy, had passed away in 1966 and his family saw

him becoming lonelier and more depressed.

More and more, the time with his brother seemed to be the only thing to

bring a smile to a man renowned for his generosity and good nature.During dinner, Jimmie Foxx collapsed with an apparent

heart attack (he had suffered two others in recent years) and was rushed to

Miami Baptist Hospital, where attempts to revive him failed. An autopsy later revealed that Foxx had

choked to death, in a fashion similar to that of his wife several months

earlier. Broken-hearted, Sam Foxx died

just a few weeks later. The sad end to

Foxx’s life does not diminish what is in many ways a classic American

Story. He rose from a Maryland farm boy

who came from little to reach the heights of fame and fell back to earth

again. However, throughout it all he was

able to keep the personality and appeal that still drew praise from his former

teammates long after they played with him.

James Emory Foxx was born in Sudlersville, Maryland,

on October 22, 1907. His parents Dell

and Mattie were moderately successful tenant farmers. Dell Foxx had played baseball for a town team

in his youth and instilled a love for the game in his eldest child (brother Sam

would arrive in 1918). According to

family legend, Jimmie tried to run away and join the Army at the age of 10,

after hearing his grandfather’s military exploits in the Civil War. Young Jimmie did reasonably well in school,

but truly excelled in athletic pursuits, including soccer and track as well as

baseball. His many hours of work on the

family farm would build up a fabled physique that belied his average-sized 5

foot 11’ frame. He set several local

records in track events as a schoolboy, and always kept deceptive foot speed;

teammate Billy Werber, and ace base stealer himself, maintained that Foxx was

always one of the faster runners in the league.

In 1924, the expansion of the Eastern Shore League

brought a team to nearby Easton. The

franchise attracted added attention due to its player-manager, Frank “Home Run”

Baker, a future Hall of Famer and local hero from Trappe, Maryland. Foxx’s baseball exploits for Sudlerville High

quickly came to Baker’s attention, and he invited Foxx for a tryout. Showing up in a pair of overalls, the high

school junior told Baker he could catch for him if needed to do so and was

signed for a salary estimated at between $125 and $250 a month. Foxx played for Easton throughout the summer,

hitting .296 with 10 home runs. At the

end of July, the Philadelphia Athletics bought his contract, and he even went

up to the big club to watch the end of the regular season from the bench. After the season, he returned to Suldersville

and his senior year of high school – after all, the young slugger was only 16!

The schoolboy athlete did not finish that senior year,

leaving in the winter to attend spring training with the Athletics. Foxx stuck with the team as a pinch hitter

and reserve catcher, singling in his major-league debut against Washington’s

Vean Gregg on May 1, 1925. To get him

some more playing time, manager Connie Mack sent Foxx to Providence of the

Eastern League, where he hit .327 despite missing time with a shoulder

injury. He returned to the team in

September, although injuries continued to keep him on the bench. Still, he had a nifty .667 batting average in

his first 10 major-league games, certainly an auspicious debut. He stuck with the Athletics for the 1926

season, but again saw little playing time.

The team already had a gifted young catcher in Mickey Cochrane, which

relegated Foxx to pinch-hitting and spot duty in the outfield.

By 1927 Connie Mack was beginning to build a

powerhouse. The Ruth/Gehrig Yankees

still reigned supreme, and the Athletics were only able to finish a distant

second that season. Mack had carefully bought

younger players such as Foxx, Cochrane, pitcher Lefty Grove, and outfielder Al

Simmons, and brought in veterans Ty Cobb (in 1927) and Tris Speaker (in 1928)

to supply experience and guidance to his youthful stars. Foxx again spent most of the season on the

bench, hitting .323 in a limited role.

However, this season was significant in that he began playing first base

most of the time. Foxx settled in at

first base for the bulk of his career and was an underrated fielder with better-than-average range. He also occasionally

caught and sometimes manned third base, a position he played in several

All-Star games because of the presence of Lou Gehrig at first. In 1928 the A’s, a mixture of young stars and

old, gave the Yankees everything they could manage before falling just short of

the pennant. Foxx became a regular at

last, playing first and third and getting off to a torrid .407 start by

June. He cooled off in the second half

of the season, settling for .328, but was now clearly a rising star. In the offseason, he celebrated the turn in

his fortunes in two ways. He brought his

parents a new farm outside Suldersville, and he eloped with his girlfriend

Helen Heite, with whom he would have two sons and a tempestuous 14-year marriage.

In 1929 the Athletics blossomed into a legendary

juggernaut, romping to an easy pennant, finishing 18 games ahead of the

Yankees. Foxx, playing mostly at first

base now, had his first wonderful season.

Throughout August, he was leading the league in hitting at .390 and

running neck-and-neck with Ruth and Gehrig for the lead in home runs. A September slump cost him the batting title

to Lou Fonseca (Foxx ultimately finished 4th), but he still pounded

the ball to a .354 tune with 33 round-trippers.

His on-base percentage of .463 led the league. The A's advanced to the World Series to face

the Chicago Cubs.

Foxx’s first child, Jimmie Jr., was born just before

the Series and he told the press that he would hit a home run for him. He kept that promise by homering for the A’s

first run of the Series in Game One and also went deep in Game Two. Foxx delivered a key single in the famous

10-run rally that won the fourth game, and the A’s went on to win the Series in

five games. The championship season

brought plenty of attention to the 21-year-old slugger, and he was feted

royally in Sudlersville in celebration.

The 1930 season brought more of the same to Foxx and

the Athletics. The team took a bit

longer to put away its competition, this year coming from Washington, but it

repeated as American League champions. A

torrid early season was again the fashion for Foxx, as he hit 22 home runs, and

was one of four A’s players to have an on-base percentage over .420.

The 1930 World Series pitted the A’s against the St.

Louis Cardinals, and they battled to a 2-2 tie going into Game Five at

Sportsman’s Park. The game was scoreless

into the top of the ninth inning. With

one on, Foxx announced to his teammates that he would “bust up the game right

now.” He then went ahead to hit a

Burleigh Grimes pitch in the left-center-bleachers, giving the A’s the win and supplying

the impetus for them to wrap up the Series in Game Six. The game-winning home run gave Foxx one of

his proudest moments and he later cited the blow as one of the greatest moments

of his career.

Off the field, Foxx continued to enjoy his favored

childhood pastimes of hunting and fishing.

He often took extended hunting forays with his teammates in the

offseason, between barnstorming trips. Some

newspapers reported Foxx to be a moderate eater who watched his diet during the

season, but he also was known to tip the clubhouse boy famously for bringing

him huge meals before and after the games.

When he returned home to Maryland, he often indulged in backwoods

country feasts, including lifelong passions for Virginia ham and homemade peach

ice cream. He enjoyed movies and

collected autographed photos from his favorite stars, with Katharine Hepburn

tops on the list. (In 1996, a

Philadelphia newspaper ran an article linking Foxx romantically to actress Judy

Holliday, but this was later revealed to be a hoax.)

The press took a liking to Foxx, dubbing him with

various nicknames-“Double X,” – “The Maryland Strong Boy,” or simply “The

Beast.” He was often depicted as a

simple country boy, unaffected by the bright lights of the big city. Nonetheless, he did develop some expensive

big-city habits. Foxx spent large sums

on the best clothes money could buy, a tendency shared by his wife, Helen. He also had a fondness for personal grooming,

often visiting his manicurist during the season. As his salary grew, so too did his generosity

and profligate spending. The star

slugger gave handsome tips to everyone from the bellhop to the batboy, and he

insisted on picking up the entire tab at every dinner and outing. He was known

to literally give the shirt off his back if someone asked him for it. Many years later, Foxx’s former teammates and

opponents still spoke with reverence of his personal kindness and goodwill.

After winning consecutive World Series, the Athletics

had an even better regular season in 1931.

The team won 107 games and cruised to the pennant easily despite

competition from a Yankees team that scored nearly seven runs per game. Foxx continued to play a key role but was

hampered by serious knee and foot injuries, as well as the beginnings of sinus

trouble that would haunt him in later years.

Still, he hit 30 home runs and had 120 runs batted in, the third of 12

consecutive seasons of over 30 home runs.

In the World Series, the A’s again faced the Cardinals, but this time

Philadelphia was upset mainly because of the storied exploits of Cards outfielder

Pepper Martin. Foxx hit .348 in the

Series and smashed a ball completely out of Shibe Park in Game Four. In his three postseason appearances, Foxx hit

.344 with four home runs. However, the

1931 World Series was the last one for Foxx and the Philadelphia Athletics.

the 1932 campaign did not bring another pennant to

Philadelphia, but Foxx thrilled fans home and away by making an epic run at

Babe Ruth’s single-season record of 60 home runs. By the first week in May, he had belted 19

round-trippers, and he reached 41 by the end of July, a month ahead of Ruth’s

pace. In August, Foxx injured his thumb

and wrist in a household accident, and although he played through the injury

it hampered his power output. Going into

the last weekend of the season, Foxx had hit 56 homers, and he tried his best,

hitting two more in the final two games.

His total of 58 fell just short of Babe’s mark – but it is important

to note that conditions for Ruth were a little easier in 1927. In the intervening

five years, screens had been erected in St. Louis, Cleveland, and Detroit that

reduced the number of home runs in those ballparks. In an interview with Fred Lieb after the

season, Foxx said that he had lost 6 home runs to the screens in St. Louis

alone. In any event, 1932 stands as the

peak year of Foxx’s career. Aside from

his 58 round-trippers, he led the league with 169 runs batted in and narrowly

missed the batting title with a .364 mark.

After the season, he was named the American League’s Most Valuable

Player.

After the season, Mack began the dismantling of his championship

team. Declining attendance and personal

financial woes due to the Depression left Mack desperate for money, and he was

forced to sell off the only valuable asset he owned: the stars of his ball club. Al Simmons was the first to go, followed by

Grove, Cochrane, and other starters from the three pennant-winning teams. Only Foxx remained through the first three

seasons of Mack’s fire sale, and he put up three more great seasons throughout

it all. In 1933, the Athletics still had

enough left to finish third, helped in large part by Foxx’s second straight MVP

campaign. Playing through a series of

leg ailments, Foxx hit 48 home runs with a .356 average and 163 runs batted in,

giving him the Triple Crown that had narrowly evaded him in 1932. He was selected to play in the first All-Star

game, and he hit for the cycle against Cleveland on August 14. After the season, Foxx battled with Mack over

a pay raise (he eventually received a slight increase, to $18,000) and

published a book, How I Bat. The

ghostwritten volume attributed his batting success to developing his wrist

muscles and getting plenty of practice.

The Athletics further eroded in 1934, but again Foxx

provided them with most of their season’s highlights. For the third straight year, he hit over 40

home runs and even stole a career-high 11 bases. The most significant events of 1934 for Foxx

came after the season. In an exhibition

game in Winnipeg, a pitch thrown by minor-leaguer Barney Brown struck Foxx on

the forehead and knocked him unconscious.

He spent four days in the hospital and was considered “recovered” when

released. However, he suffered from

sinus problems for the rest of his life, which in turn led to extreme

difficulties on and off the field.

Despite this setback, Foxx was allowed to go with Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig,

and other all-stars on a historic tour of Japan in November.

To help cover the loss of Cochrane, Foxx returned to

his original position behind the plate to start the 1935 season. He had a strong arm and by all accounts managed

pitchers well, but eventually moved back to first and third because of injuries

to other players. The Athletics fell all

the way to the cellar, but not without another strong year from its last

remaining star. Foxx tied Hank Greenberg

for the league lead with 36 homers and finished only three points behind in the

batting title race. After the season,

the long-rumored trade of Foxx finally came to fruition. Boston Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, who had

already bought Grove from Philadelphia and player-manager Joe Cronin from

Washington in recent years, paid Mack $150,000 for Foxx and pitcher Johnny

Marcum (two minor players, Gordon Rhodes and George Salvino were also included

in the deal). Foxx reacted positively to

the deal; no doubt helped by a $7,000 increase in salary.

The highlight of Foxx’s first season in Boston came on

June 16, when he hit a ball completely out of Comiskey Park. (In later years, pitchers Lefty Gomez and Ted

Lyons enjoyed spinning yarns about the tape measure shots Foxx hit off

them.) this was one of 41 home runs that

season, and although he did not lead the league in any of the power categories,

Foxx’s performance was one of the bright spots of a disappointing season for

the Red Sox. In 1937, sinus problems

brought his performance down dramatically.

Foxx went through homerless streaks of 16 and 24 games and hit a mere

.285, the lowest average of his career up to that date. Although he topped his Comiskey Park blast by

hitting a ball out of Fenway Park to the right of the center field flagpole

against the Yankees on August 12, speculation began that his career was on the

downslide.

In 1938, Foxx silenced his critics with one of his

greatest seasons. He proved that his

power had not diminished by hitting five home runs in the last week of the

exhibition season. In May, he hit 10

home runs and drove in a whopping 325 runs.

Other highlights followed, including a game on June 16 in which he was

walked six times, tying a major league record.

The Yankees eclipsed the Red Sox in the standings, and Foxx’s home run

totals came in second to Hank Greenberg’s run at Ruth’s record. Still, when the dust had settled over the

1938 season, Foxx had won two-thirds of another Triple Crown, batting .349 and

driving in 175 runs, the fourth-highest total of all time. Thirty-five of Foxx’s 50 home runs were hit

at friendly Fenway Park, setting up what was then a record for homers hit at

home. His RBI totals still stand as a

Boston Red Sox team record, and his home run total was not surpassed by a Red

Sox player until David Ortiz in the 2006 season. After the season, Foxx beat out Greenberg in

the voting to take home his third American League MVP award.

The 1939 season brought a new star to the Red Sox, a

raw rookie named Theodore Samuel Williams.

Williams had boasted to his new teammates, “Wait until Foxx sees me

hit!” – but he also looked to the veteran slugger as a mentor and even a father

figure. In later years, Williams told

his younger teammates stories about Foxx’s slugging and pointed out places in

the ballparks where Foxx had hit tape-measure home runs. The friendship between the two men lasted

until the end of Foxx’s life, and Ted remained close to his teammates’ family

until his death in 2002. Together the two

sluggers formed a powerful left/right combo that brought the Red Sox into

pennant contention for most of the 1939 season.

Foxx enjoyed another superb season, batting .360, second in the league,

and leading the AL with 35 home runs.

His great year concluded a remarkable decade in which he was arguably

the game’s dominant hitter. From 1930 through 1939, Foxx slugged 415 home runs

and drove in 1,403 runs.

During his years with the Red Sox, Foxx moved into a

hotel and was separated from his family for long periods. It was during this period that the first

signs of his drinking problems appeared.

Although known to imbibe occasionally, he was never reported to be a

heavy drinker during the early years of his career. After his beaning, his sinus problems brought

him acute pain – a pain that subsided with alcohol. Roommate Elden Auker recalled several nights

when Foxx would be plagued by severe nosebleeds. His ample free time in Boston led to

increased after-hours activities, and he bragged to Ted Williams about the

amount of scotch whiskey he could consume without being affected. A teammate of the Chicago Cubs remembered

that a walk back from the ballpark to the team hotel with Foxx was fraught with

dangerous opportunities, as the veteran enjoyed visiting each of his favorite

taverns along the way.

Although his drinking problem is a matter of record,

it is important to point out that Foxx was never noted for violent or aggressive

behavior. To the contrary, he was known

as a gentle peacemaker, often mediating disputes in card games and making sure

rookie roommate Dom DiMaggio got to bed on time. Tom Yawkey enjoyed Foxx’s company and shared

many of his favorite activities.

According to one story, the player avoided a fine from Joe Cronin for

missing a curfew when he returned to the hotel lobby in the early morning with

the owner in tow. Some have surmised

that the length of Foxx’s career was curtailed by his drinking, and it

certainly did not help. It seems much

more likely that it was diminished batting eye caused by the beaning and

related sinus problems that led to his decline.

Foxx also often played through injuries that would have sidelined other

players, and eventually, this took a toll as well.

Foxx stayed an all-star slugger in 1940 and 1941,

driving in over 100 runs both years and hitting a total of 55 home runs. His triple allowed longtime teammate Lefty

Grove to win his 300th game in 1941.

Foxx had been eclipsed by Williams as the team’s star and was showing

signs of slowing at the plate and in the field.

His sinus problem became more acute, and he began to wear eyeglasses off

the field to combat a decline in his vision.

In addition, he grew more critical of player-manager Joe Cronin. Although Foxx got along well with everybody,

he never had the respect for Cronin that he had for Mack, and some tension

developed (to his credit, Cronin interceded in Foxx’s life in later years with

offers of employment and financial aid).

When the 1941 season ended, it was no secret that Foxx’s days with the

Red Sox were coming to an end.

Off the field, Foxx’s marriage to Helen had

unraveled. According to Elden Auker, she

constantly harassed Foxx via phone over financial issues, while all the time

carrying on an extramarital affair.

Their divorce became final in early 1943, with Helen accusing Foxx of

selfishness and other forms of mental cruelty.

The acrimonious divorce resulted in a long estrangement between Foxx and

his two young sons, James Emory Jr. and W. Kenneth. Both were sent to military schools and

seldom if ever spoke to their father. Kenneth

did not reunite with his father until his stepmother’s funeral in 1966, and

Jimmie Jr. essentially disappeared in the 1950s after serving in the Korean

War. For many years his family believed

that he was deceased; however, he resurfaced in the Philadelphia area and

renewed contact with his siblings just a few years before he died in 2006.

As the 1942 season began, Cronin told Foxx that he

would have to win the first base job from young Tony Lupien. Despite breaking a toe in spring training,

Foxx outhit Lupien and started the season as a regular. Just as he was beginning to hit again, a

freak batting practice injury resulted in a broken rib. On June 1, the Red Sox placed Foxx on

waivers, and he was sold to the Chicago Cubs for a mere $10,000. The move caused great regret and sadness for

both Boston players and fans, but Foxx’s days as a productive player were

over. He hit only .205 for the Cubs the

rest of the year and announced his retirement at the end of the season.

He stayed out of baseball during 1943, a year

highlighted by his second marriage, to Dorothy Yard. Foxx and Dorothy enjoyed a warm and committed

relationship through thick and thin until her untimely death in 1966, and he

became a true father to her two children, John and Nanci, as well. In 1944, Foxx volunteered for the military but was rejected due to his sinus condition.

He returned to play a handful of games as a player-coach for the Cubs

and also became interim manager of Portsmouth in the Class B Piedmont League.

The final go-round for Jimmie Foxx’s major league

career came in the city where he had starred for so long – Philadelphia. This time it was the Phillies, who were

looking to fill out their roster in the tight wartime era. Foxx was invited to spring training and after

hitting several home runs made the team as a pinch-hitter. By this time, he was having increasing

difficulty with his eyes and also suffered from shin splints and

bursitis. Tony Lupien, who had followed

Foxx at first base for the Red Sox, also played for the Phillies in 1945 and

remembers Jimmie as being particularly down on himself in this period. However, another teammate, Andy Sminick,

remembers Foxx as his usual fun-loving, generous self all year, often inviting

Andy to his home for big fried chicken dinners.

Foxx hit the last seven home runs of his career for

the Phillies, but what made his final season unique was his turn on the

pitching mound. Volunteering to help the

team out in any way he could, Foxx pitched 23 innings, with a 1-0 record and a

1.59 ERA. His high point on the mound

came in the second game of a doubleheader on August 19, when Foxx pitched

five no-hit innings in an emergency start.

(He had pitched once very briefly while with the 1939 Red Sox.) his last major league at-bat came against the

Dodgers on September 23. At the close of

the season, Foxx retired for good, with a .325 lifetime batting average, 2,646

hits, and 534 home runs – a total that was second to only Ruth until 1966. His total of 1,922 runs batted in still

ranked at 8th all-time in 2008.

The end of his playing career stood for a dramatic

transition in Foxx’s life. He was now

happily remarried with a new son, also named Jimmie Jr., but his divorce from

Helen had been damaging to his finances, and he had lost thousands in an

investment in a Florida golf course that closed because of World War II

restrictions. For the rest of his life,

he struggled mightily at times to find a steady career outside of baseball, yet

his teenage rise to the majors had left him with little preparation to do

so. He took a turn in the Red Sox radio

booth in 1946, but his Maryland accent did not win over many listeners. He also spent brief periods as a minor-league

manager and coach in St. Petersburg in 1947 and Bridgeport, Connecticut in

1949, and worked for a trucking company and beer distributor.

Foxx had received Hall of Fame votes as far back as

1936 when active players were eligible (he came in fourth then among active

players behind Rogers Hornsby, Mickey Cochrane, and Lou Gehrig.) However, he fell short of the needed vote

totals in six other regular and run-off elections until 1951. Foxx was named on 79.2% of the ballots and

earned election along with the leading vote-getter Mel Ott. in a brief speech, he merely noted that he

was proud to be a member and proud to have his old manager, Connie Mack on

hand. After the ceremony, he spent most

of his time under a tree signing autographs.

Foxx generally enjoyed giving autographs throughout his life, although

toward its end he sometimes had to use a rubber stamp to keep up with all of

the many requests forwarded to his home.

His family members remember frequent occasions when he would leave the

table at restaurants to accommodate his fans.

Foxx got back into baseball in 1952 in an unusual

manner when he was invited to manage the Fort Wayne Daisies – a team in the

All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. He succeeded fellow Hall of Famer Max Carey,

who had become the league president and was offered a $3,600 salary with

bonuses. By all accounts, Foxx's time with

the Daisies was an enjoyable one. With

daughter Nanci helping out as a batgirl, the team improved attendance and made

the playoffs. In 1992, the film A

League of Their Own based the team’s manager (played by Tom Hanks_

loosely on Foxx, although the women who played for him remember him only as a

true gentleman in every way. Foxx did

not return to the Daisies for the 1953 season, with his only complaint being

the many long bus rides.

After his turn with the Daisies, the retired slugger

continued to drift from job to job. At

various times, he worked as a car salesman, for an oil company, and even as a

coal truck driver. An ambitious venture

in which Foxx was to do public-service work with inner-city youths did not get

off the ground. In 1956, he returned to

Florida and spent two seasons as a head baseball coach at the University of

Miami and as a hitting instructor for the minor league Miami Marlins. After the 1957 season, he was let go from

both positions and found himself bankrupt and unemployed. Invited to speak at the Boston Writers Dinner

in January 1958, Foxx admitted that he was broke and unable to pay his way

there. All his baseball earnings, he

announced, were long gone. After his

financial problems were shown, Foxx received many offers of employment and even

cash donations (which he then donated to the Jimmy Fund). Soon, a good fit was found. After a meeting with Cronin in Boston, Foxx

accepted a job as the hitting instructor for the Red Sox’s Triple-A farm team,

the Minneapolis Millers.

Although he seldom took batting practice, saying that

he “couldn’t do it” anymore, Foxx was well-liked and admired by the Millers

players. One player he befriended was

Bill Monbouquette, a young pitcher on the brink of a solid major-league career

that included a no-hitter for the Red Sox in 1962. Monbouquette remembers Foxx as a generous and

giving man, “one of the nicest people I’ve ever met.” Both pitchers and hitters picked his brain

constantly for tips and advice, and Foxx was always glad to advise. During the season, Foxx surprised

Monbouquette’s while on the way to Fenway Park old-timers game. “I just wanted to let them know you were

doing okay,” Foxx told the young pitcher on his return.

However, Foxx’s tenure with the Millers lasted only a

single season. Art Schult, the Millers

catcher, recalled that the players “idolized” Foxx, but that he did not get

involved in the politics of the game with management. During the season, he was twice hospitalized

with high blood pressure and other ailments.

Expecting to return to the Millers for 1959, Foxx was instead given his

release by the Red Sox at the end of the 1958 season. The official reason given was that the team,

for financial reasons, wanted to hire someone to do double duty as a player and

coach.

The real reason, however, had more to do with Foxx’s

off-the-field habits. Gene Mauch, the

Millers’ manager in 1958, recalled jumping at the chance to hire Foxx, a

boyhood favorite and felt he could help out the team’s hitters. Sadly, things did not go as planned. According to Mauch, “By then, Jim had a bad

drinking problem and was seldom at the park on time to be of help. I idolized the man and kept him away from

scrutiny. At the end of the season,

Cronin gave him his money and sent him home – it was so sad.” Foxx’s drinking habits were also rumored to

have led to the end of his coaching in Miami and may have affected his

employment elsewhere. His alcohol use

may have stemmed from his sinus injury and worsened by his good-time lifestyle

in Boston. However, at this point, Foxx’s

drinking was related as much as anything to the loss of his baseball

career. Daughter Nanci believes his

drinking problems had a lot to do with the emptiness he felt in adjusting to

normalcy once his playing days had ended.

The ill-fated season in Minneapolis was Foxx’s last

job in baseball. He did occasionally

appear at old-timers’ games and was interviewed when Willie Mays passed him on

the all-time home run list (Foxx applauded Mays, saying it was great to see it

done by a fellow right-handed hitter). A

restaurant bearing his name in Illinois quickly went under, and he continued to

move around, bouncing from work with a sporting goods store in Lakewood, Ohio,

to several part-time jobs in Florida when he returned there in 1964. His son, Jimmie Jr. II, stayed in Ohio to

pursue an athletic career at Kent State University. Health problems continued to plague the elder

Foxx; he suffered two minor heart attacks, and his mobility was lessened by a

back injury suffered in a fall.

In May 1966, he suffered a terrible personal blow when

his wife, Dorothy, died of asphyxia.

Throughout the good years and bad, the two had a strong and devoted

marriage, and after her passing, depression seemed to get the better of

Foxx. He returned to Maryland one last

time in August 1966 to surprise a fan, Gil Dunn, who had written him concerning

a memorabilia display in his drugstore near Sudlersville. The slugger again gave Dunn a variety of

uniforms, equipment, and trophies, and with brother Sam in tow made the rounds

of his old hometown one final time. The

locals had turned a cold shoulder to Foxx in his retirement years; a strong sign

of this came when several local establishments refused to cash a $100 check,

later proven good in a neighboring town.

Less than a year later he was dead at 59 and was buried next to Dorothy

in Miami’s Flagler Memorial Park Cemetery.

In the years since Foxx’s death, a gradual

re-appreciation of his achievements has elevated his status. As a member of baseball’s 500 Home Run Club,

Foxx memorabilia fetches top dollar on the collector circuit. The Babe Ruth Hall of Fame and Museum has

devoted exhibit space to Foxx, thanks in part to donations from Gil Dunn. In the past few years, Foxx has been honored

by the Oakland Athletics and was inducted into the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame,

each time with daughter Nanci proudly on hand to accept for him. He was one of the first players chosen by old

teammate Ted Williams to be enshrined in his own Hitters Hall of Fame. Foxx even made it onto a U.S. postage stamp

in the summer of 2000. In September

2006, Foxx returned to the Fenway limelight once again. David Ortiz, another perpetually smiling Red

Sox slugger, broke his 68-year team home run record with Nanci in attendance.

Perhaps the greatest tribute though, came from his

hometown of Sudlersville, Maryland. A

monument to Foxx was erected in celebration of his 80th birthday in

1987, and after 10 years of fundraising, a bronze life statue was unveiled on

October 25, 1997, in the center of his hometown. The Maryland Strong Boy had come home for

good.

Sources:

"My research on Jimmie Foxx’s life began about the same time I joined SABR in 1993. Writing

this biography entailed the use of primary, secondary, and interview sources. In

addition, I am grateful to the aid of Mark Armour, Harrison Daniel, Peter Golenbock, Bob

Gorman, Mark Hodermarsky, Bill Nowlin, Fred Schuld, and Dick Thompson (among others)

in the preparation of this narrative."

1. Auker, Elden. Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms.

Triumph Books, 2000.

2. Canaday, Nanci (as told to John Bennett). “My

Dad- Jimmie Foxx”, The National Pastime,

Number 19, 1999.

3. Daniel, W. Harrison, Jimmie Foxx: The Life and

Times of a Baseball Hall of Famer McFarland,

1996.

4. DiMaggio, Dominic, and Bill Gilbert. Real

Grass, Real Heroes: Baseball’s Historic 1941

Season. Kensington, 1991.

5. Golenbock, Peter. Fenway: An Unexpurgated

History of the Boston Red Sox. Douglas

Charles, 1991.

6. Hall of Fame Files, Jimmie Foxx (volumes

1, 2, 3), National Baseball Hall of Fame and

Library, Cooperstown, New York.

7. Gorman, Bob. Double X: The Story of

Jimmie Foxx, Baseball’s Forgotten Slugger

B. Goff, 1990.

8. Linn, Ed. The Great Rivalry. Ticknor and

Field, 1991.

9. Millikin, Mark. Jimmie Foxx: The Pride of

Sudlersville. Scarecrow Press, 1998.

10. Williams, Ted, with John Underwood. My

Turn At Bat: The Story of My Life. Fireside,

1988.

11. Werber, Bill. Memories of a Ballplayer.

SABR Press, 2001.

12. In particular, I wish to cite the three

biographies of Jimmie Foxx, all of which

have their own special strengths. They were

extremely useful resources and should be the

first place for a Foxx enthusiast to go.

13. I was able to interview the following former

players by phone mail, and/or in person

between 1993-200, several of whom are directly

quoted within:

A. Elden Auker.

B. Dom DiMaggio.

C. Bob Doerr

D. Bob Feller

E. David “Boo” Ferriss

F. Tom Henrich

G. Tony Lupien

H. Gene Mauch

I. Lenny Merullo

J. Bill Monbouquette

K. Johnny Pesky

L. Art Schult

M. Andy Seminick

N. Charlie Wagner

O. Bill Werber

P. Alma Ziegler

"Last and certainly not least, I wish to personally note and thank the aid of Jimmie’s daughter, Nanci Foxx Canaday, who has been instrumental in my research on Foxx for 10 years now. Along with her husband, Jim, she welcomed me into her Florida home for an interview on June 30, 2000, and continues an annual correspondence. Nanci supplies living proof of Jimmie’s best qualities, and none of my work would have happened without her help."

Full Name: James Emory Foxx.

Born: October 22, 1907, at Sudlersville, MD (USA).

Died: July 21, 1967, at Miami, FL (USA).