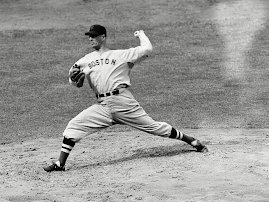

Lefty Grove may have been baseball’s greatest all-time

pitcher. He was certainly its most

dominant. No one matched his nine ERA

titles, and his .680 winning percentage (300-141) is the highest among 300 game-winners (eighth best overall). After

winning 111 games in a minor-league career that delayed his major-league debut

until he was 25, Grove led the American League in strikeouts his first seven

years, pitched effectively in hitters’ parks (Shibe Park, Fenway Park) and

starred in three World Series. Few if any

pitchers threw tantrums on a par with the 6’3”, 190-pound Lefty, who did

everything big. He even led all pitchers

by striking out 593 times as a batter.

Robert Moses Grove was born to John and Emma Grove on

March 6, 1900, in the bituminous mining town of Lonaconing, Maryland. His father and older brothers preceded him

into the mines, but Lefty quit after two weeks, saying, “Dad, I didn’t put that

coal in here, and I don’t have to take no more of her out.”

Lefty drifted into other jobs: as a “bobbin boy”

working spinning spools to make silk thread, as an apprentice glass blower and

needle etcher in a glass factory, and as a railroad worker laying rails and

driving spikes. In his spare time, he

played a kind of baseball using cork stoppers in wool socks wrapped in black

tape, and fence pickets when bats weren’t available. he did not play genuine baseball until 17,

nor genuinely organized baseball until 19, when Dick Stakem, proprietor of a

general store in nearby Midland, began using him in town games on a field

sandwiched between a forest and train tracks.

“Bobby never pitched a game [for Midland] until Memorial Day, 1919,”

Stakem told the Philadelphia Bulletin’s John J. Nolan. “He pitched a seven-inning game which was

ended by rain. He fanned 15 batters,

walked two men, hit two, and made a wild pitch.”

“Here’s the scorebook to prove it.”

“Bob’s best games was a postseason series against [the

Baltimore & Ohio railroad team in] Cumberland, the big team around here….

We went down there with Bobby, and he held them hitless, fanned 18 batters, and

the only man to reach first eventually got around to third. The reason he got there was because Bobby

told me he let him steal second and third as he was so sure he could fan the

next batters and the runner wouldn’t steal home. The score was 1 to 0, the other pitcher

allowing just one hit.”

The B & O manager supposedly wanted Grove, and the

next year Bob was cleaning cylinder heads of steam engines for B & O in

Cumberland, Maryland. Before he could

put in a baseball season there, a local garage manager named Bill Louden, who

managed the Martinsburg, West Virginia, team of the Class D Blue Ridge League,

offered him a princely $125 a month, a good $50 more than his father and

brothers were making. With his parents’

blessing, Lefty took a 30-day leave from his job, signed a contract on May 5, got

a roundtrip rail pass from his master mechanic, and was driven across the

mountains in a large car supplied by the Midland team. While Grove was going 3-3, with 60 strikeouts

in 59 innings, word reached Jack Dunn, owner of the International League

(Double-A) Baltimore Orioles. Dunn sent

his son Jack Jr. to watch Grove. As it

happened, the Martinsburg team had started the season on the road because it

lacked a fence around the home field. Dunn

bought Grove for a price in the $3,00 - $3,500 range that satisfied

Louden. “I was the only player,” Grove

said later, “ever traded for a fence.”

According to some accounts, the Orioles signed Grove

just ahead of the Giants, Dodgers, and Tigers overtures. It will forever be debated how many

major-league games Grove would have won if he hadn’t spent five seasons with

the Orioles. We’ll never know the

answer, but we do know that Grove enjoyed playing for the Orioles. Starting at $175 a month, he won his debut,

9-3, over Jersey City, prompting owner Dunn to say he wouldn’t sell Lefty for

$10,000. In 1920-24, Grove was 108-36

and struck out 1,108 batters for a minor-league record, though he was often

wild and went 3-8 in postseason play. By

his last season in Baltimore, however, Grove was certainly pitching like a

major leaguer. He went 26-6 despite

missing six weeks with a wrist injury, struck out 231 batters in 236 innings, and reduced his walks from 186 to 108.

Moreover, Grove routinely struck out between 10 and 14 major leaguers in

exhibition games (they may have been reluctant to dig in against him), told

Babe Ruth “I’m not afraid of you,” and made good his boast by whiffing the

Bambino in nine of 11 exhibition at-bats.

With no minor league draft in the 1920s, Dunn could

wait for the best offer before selling Grove to the majors. By the 1924-25 offseason, he couldn’t

resist. The Cubs and Dodgers offered

$100,000, according to the Philadelphia Evening Ledger, but Dunn

sold Grove to an old friend, Philadelphia owner/manager Connie Mack, for

$100,600. The extra $600 supposedly made

it a higher price than the Yankees paid the Red Sox for Babe Ruth after the

1919 season – higher if you discount notes, interest on notes, and a $300,000

loan that swelled the Yankees’ cost to more than $400,000.

The much-ballyhooed sale backfired on Grove, who was

called the “$100,600 Lemon” when he went 10-12 in 1925 and led the American

League in both walks (131) and strikeouts (116). He was too pumped up and overthrowing as he had

in the postseason with Baltimore.

“Catching him was like catching bullets from a rifleman with bad aim,”

the Athletics’ catcher Mickey Cochrane told sportswriter Frank Graham years

later. Nonetheless, Mack stuck with him,

and Grove, taciturn and sullen during the season, returned home with a

mission. “Huh, so I’m the wild guy of

the league?” Grove said to the Evening Bulletin’s Nolan, who had taken

an 11-hour train ride from Philadelphia.

“I’ll show’em something next year.

See that chalk mark on the barn door.

I measured off sixty feet. I

reckon it is, and at six o’clock every morning I hit the chalk mark twenty

times before I quit. Then I tramp the

hills hunting and cover about twenty miles a day.”

Up at 5:30 AM, asleep by 9 PM, Grove was rested and

ready for spring training. Though he was

only 13-13 in 1926, his ERA dropped from 4.75 to a league-best 2.51, his walks

dropped from 131 to 101 and his strikeouts climbed from 116 to an AL-best

194. A victim of non-support, he was

shut out four times in the season’s first two months. To Yankees manager Miller Huggins, Grove was

night-and-day improved over 1925: “Now he has wide bending curves, better

control, is mentally fit, has a lot of confidence and plenty of natural

ability,” Huggins said. “He mixes his

speed and curves and he’s the speediest pitcher in baseball.” Huggins could afford to be generous because

Grove did not beat the Yankees when they pulled away from the pack in

September. It was a pattern that would

repeat.

Grove led the league in strikeouts for the next five years

and won 20 or more games for the next seven.

Alas, there was no catching the 1927 Yankees, and Grove lost six of his

last seven decisions to them in a heartbreaking 1928. A Babe Ruth homer in a decisive September

tilt especially victimized Grove.

However, both he and the Philadelphia club, 2 ½ games back of the

Yankees at 98-55, were poised for greatness.

In 1929, the Athletics broke through. Grove was 2-1, with one save, against the

Yankees, 20-6 overall, and the A’s won the pennant. Apparently fearing the Cubs’ right-handed hitters,

Mack declined to start either Grove or fellow lefty Rube Walberg in the World

Series, but Grove made his mark in relief.

After Howard Ehmke won the opener, 3-1, Grove replaced a struggling

George Earnshaw in Game Two with two outs in the fifth, two men on base, and

the A’s leading 6-3. Grove fanned Gabby

Hartnett on five pitches and finished with six strikeouts, three hits, one

walk, and no runs allowed over 4 1/3 innings.

For some reason, Earnshaw was given the win; Grove had to enjoy the

greatest long-relief save in Series history.

“How can you hit the guy,” Hartnett asked, “when you can’t see him?”

In historic Game Four, when the A’s rallied from an

8-0 deficit to win, 10-8, Grove pitched the last two innings in relief. The A’s took the Series, four games to one,

and Grove struck out 10 batters in 6 1/3 innings. “When danger beckoned thickest,” Heywood Broun wrote, “it was always Grove who

stood towering on the mound, whipping over strikes against the luckless Chicago

batters.”

Thanks to Mack, who had convinced Grove to move some of his money to a bank that wasn’t later closed down, Lefty survived the stock

market crash. Indeed, he spent $5,700 to

build Lefty’s Place, a Lonaconing establishment with three bowling alleys, a

pool table, and a counter filled with cigar cases, candy, cigarettes, and soft

drinks. Terse at tributes his honor,

Grove quietly employed his brother, Dewey, out of work since the glass factory

burned down, and his physically challenged brother-in-law, Bob Mathews. Lefty was always more comfortable with the

homefolk than city dwellers.

Grove returned to spring training in 1930 as truculent

as ever. When a rookie named Doc Cramer

doubled against him in an intra-squad game, Grove whacked him in the ribs the

next time Cramer batted. While the first-place A’s went 102-52, Grove won the Triple Crown of pitching by leading the

league in wins (28), strikeouts (209), and ERA (2.54), the latter an incredible

0.77 ahead of the next-best pitcher. He

also led the league with nine saves, though the stat wasn’t tabulated until

years later. He was excelling in clutch,

not just rolling up big numbers. In what

the Philadelphia Inquirer called “a copyrighted situation” – the A’s up

3-2, two outs, two on, and Babe Ruth at the plate in the ninth – he fanned Ruth

on a 2-2 pitch, hushing the crowd in Yankee Stadium on September 1,

In the World Series, the A’s faced the National League

champion St. Louis Cardinals, who had batted .314. The entire NL batted .303 for the 1930 season

with the Cardinals’ .314 only third best (the Cards scored the most

runs/game). Only two of the six NL teams

didn’t hit at least .300 and they each hit .281 for the season. Grove won the opener, 5-2, while throwing 70

strikes and just 39 balls, fanning five and allowing nine hits. After George Earnshaw, Lefty’s polar opposite

(right-handed, sharper breaking curve, slower fastball, a party boy), throttled

the Cards, 6-1, in Game Two, St. Louis beat Rube Walberg, 5-0, and got by

Grove, 3-1, on two unearned runs. Lefty

relieved George in the eighth inning of a scoreless Game Five and won it, 2-0,

on Jimmie Foxx’s two-run homer. At which point Earnshaw returned on one day’s rest to end the series in Game

Six, 7-1. For the series, MVP Earnshaw

was 2-0, with 19 strikeouts in 25 innings and a 0.72 ERA, while Grove was 2-1,

with 10 strikeouts in 19 innings and a 1.42 ERA.

Grove still had not had his best year. By August 23, 1931, he was 25-2 for the

season and tied for the American League record with 16 straight wins. The first-place A’s 84-32. Their opponent: the hapless St. Louis

Browns. It didn’t seem to matter that

the A’s were a little nicked up. Among other things, left fielder Al Simmons

was treated for a sprained, blistered, and infected left ankle in Milwaukee. A rookie named Handsome Jimmy

Moore replaced him. With 20,000

sweltering fans creating an unusually large crowd at Sportsman Park, Grove faces

Dick Coffman, who, with his 5-9 record, was nearly released three weeks earlier

but had saved his job by winning three straight.

Grove and Coffman kept the game scoreless through two

innings. Then came an event for which

Grove would forever be remembered. After

Fritz Schulte’s two-out bloop single in the third mildly annoyed Grove, Oscar

(Ski) Melillo unnerved him. Melillo hit

what appeared to be a routine liner to the left.

Partially blinded by the sun, Moore raced in, realized he had misjudged

the ball, and reversed course. The shot

nicked his glove and rolled to the fence, with Schulte scoring on the double.

Grove slapped his glove against his side in disgust,

got out of the inning, and returned to the dugout in muttering retreat. He righted himself to finish the game, a neat

seven-hitter with sixs K’s and no walks.

Unfortunately, Coffman was even better, getting his usually problematic

curve over and yielding just three hits.

In a stark reversal of his season-long fortunes, Grove lost, 1-0, in only

an hour and 25 minutes.

Moore never used the sun as an excuse. “If I’d stood still, I’d have caught it,” he

told the Boston Globe’s Harold Kaese 34 later. Grove didn’t blame Moore. Instead, he raged at the absent Simmons for a

good 20 minutes. In what was probably an

unprecedented display of postgame pique, Grove tried to tear off the clubhouse

door, shredding the wooden partition between lockers, banging up the lockers,

breaking chairs, and ripping off his shirt, buttons flying. “Threw everything I could get my hands on –

bats, balls, shoes, gloves, benches, water buckets, whatever was handy,” he

told author Donald Honig. If Grove couldn’t

break one record, he might as well break another.

Quickly enough, Lefty righted himself. Responding to Yankee bench-jockeying (“kicked

over ant water pails lately?”) on August 29, he struck out eight of the first

10 batters he faced. By season’s end, he

was 31-4; only three innings of grooving the ball in a final-day Series warmup

cost him an ERA under 2.00 (he finished at 2.06). winning his second straight Triple Crown with

175 strikeouts, he was named the American League’s Most Valuable Player. The Athletics won the pennant again, this

time a walk. At 107-45, the A’s were 13

½ games better than second-place New York.

With a blister on a throwing finger, Grove yielded

12 hits in the Series opener but got good fielding support and won,

6-2. “Nah the blister didn’t hurt,” said

Grove, who had to rely on curves and slowballs, “but them dinky hits they made

got me mad. I started thinking my

control was too good. You know I was

putting them right over the plate.

“I started thinking, and you know what happens when a

lefthander gets to thinking. Well, I

began to chuck up slow one and a little curve.

Every time I tossed one the Cards got ahold of it. From now on, they won’t see nuthin’ but

fastball pitching.”

The Cardinals won Game Two, and a rain delay

gave Grove several days to heal his blister.

He still wasn’t sharp. Allowing

11 hits and four earned runs in eight innings, he lost Game Three, 5-2. Earnshaw evened the Series, but then Pepper

Martin got three hits and drove in four runs, the Cardinals winning Game Five,

5-1. With the A’s on the brink of

elimination, Grove won, 8-1, on five hits and one walk. In this, his last Series appearance, he was

“pitching at the very peak of his form for the first time in this

intersectional warfare,” wrote the AP’s Alan Gould. Grove was poised for another outing, warming

up on the sidelines, when a ninth-inning A’s rally fell short in Game Seven

and the Cardinals took the clincher, 4-2.

In his three World Series (1929 through 1931), Grove

went 4-2, with a 1.75 ERA, 36 strikeouts in 51 1/3 innings and two saves. In these same seasons, he was 79-15 in

regular-season play. It was the

high-water mark for both Grove and the Philadelphia Athletics, though neither

seemed to be drowning in 1932 when the second-place A’s won 94 games and Grove

went 25-10. Used extensively in relief

the next season and totaling an exhausting 275 1/3 innings, Grove still had a

24-8 record and led the league with a .750 percentage and 21 complete games,

but his strikeouts declined from 188 to 114.

As the A’s finished third in 1933 with a 79-72 record, the word went

around the league that Grove’s arm had gone south on him.

Soon Grove was headed north. Stung by poor attendance in the Depression,

Mack began unloading his roster and traded Grove to the Boston Red Sox. Years later, summing up Lefty’s performance

with his club, Mack said Grove had been a “thrower” and never really learned

how to pitch until later. Others praised

him but as a one-pitch pitcher. “When

planes take off from a ship, they say catapult,” Yankee shortstop Frankie

Crosetti said. “That’s what his fastball

did halfway to the plate. He threw just

plain fastballs – he didn’t need anything else.”

These evaluations didn’t quite describe Grove’s

pitching. Though he relied on his

fastball, he moved it around smartly, and his curve was strong enough to

spot. As he showed in the ’31 Series, he

could even win when his fastball wasn’t working.

Grove arrived in Sarasota, the 1934 Red Sox training

camp, and was anointed team savior. They had

won 43 and 63 games in the earlier two seasons, but newsmen called them

contenders. Grove promptly announced he

wouldn’t train on Sundays – why not when young owner Tom Yawkey was in thrall

to him? Indeed, alone among the Red Sox, he

got a single room on the road.

Unfortunately, Lefty developed a sore arm in mid-March, struggled all

season, and went 8-8 with a 6.50 ERA while the Sox limped to a fourth at

76-76. The improvement of 13 games and

the record 610,640 home attendance didn’t satisfy the naysayers, too many of

whom blame Grove. Once again, he was a

lemon.

Yet he didn’t sour.

As wily and ingenious as ever, Grove spent three weeks at Hot Springs,

Arkansas during the offseason, playing 36 holes of golf a day or using a rowing

machine when it rained. He pitched only

four innings against major leaguers in spring training and proclaimed himself fully recovered for 1935. With a new approach of “curve and control,”

Grove, now 35, went 20-12 with a league-leading 2.70 ERA. The curve became his major out pitch, Grove

explained because he had lost his fastball.

“I was actually too fast to carve the ball while in Baltimore and

Philadelphia,” he said. “The ball didn’t

have enough time to break because I threw what passed for a curve as fast as I

threw my fastball. I couldn’t get enough

twist on it. …Now that I’m not fast, I can really break one off and my fastball

looks faster than it is because it’s faster than the other stuff I throw.” He paused and added, “A pitcher has time

enough to get smarter after he loses his speed.”

Grove won three more ERA titles in the next four years

while winning 17, 17, 14, and 15 games and mellowing in his behavior. That is not to say he was a model

citizen. Grove had no respect for Red

Sox manager Joe Cronin and wasn’t above saying so. In one unforgettable instance, Cronin ordered

Grove to walk Hank Greenberg with two outs, a man on second, and the Sox leading

the Tigers 4-3, in the top of the ninth.

After grudgingly complying, Grove gave up three straight singles to

trail, 6-4, at inning’s end. Leaving the

field, Grove threw his glove into the stands, ripped off his uniform, and

smashed one of Cronin’s bats before heading into the clubhouse. Amazingly, Boston won when Wes Ferrell,

pinch-hitting for Grove, hit a three-run homer.

When the happy winners told the steaming Grove the news, he silently

rolled a bottle of wine over to Ferrell.

He slipped to 7-6 in 1940, but he had won 293 games,

and no one doubted he'd reach 300 in 1941.

Oh, what a strange season it was!

In April, all baseball eyes were on Grove, but they refocused on the

pennant races and Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak before watching in awe

as Ted Williams went 6-for-8 on the last Sunday to hit .406. All this while Americans were awaiting the

latest word on approaching war clouds.

Meanwhile, Grove labored to get the big one. He had six wins by midseason. On July 25, Red Sox manager Joe Cronin told

Grove, “Pop, this is a nine-inning game.

I’m not coming out to get you.”

Cronin didn’t, and Grove survived a rock-‘em, sock-‘em slugfest to beat

the Indians on 12 hits, 10-6, with his best friend in baseball, Jimmie Foxx,

getting the decisive two-run triple. His

final win was no pathetic last gasp, some descriptions notwithstanding. Grove threw only 38 balls and walked just one

batter. The 12th 300-game

winner, the first since Pete Alexander in 1926 and the last until Warren Spahn

in 1961, earned his place in history. He

was roundly toasted at a champagne dinner party he threw for teammates that

night.

All too soon, Grove lost his last three decisions

while Boston writers told him to quit.

“A nice lesson in irony these days is to see reporters, photographers

and feature writers stumbling over such fading stars as Foxx, Cronin, and Lefty

Grove in the haste to get a Ted Williams,” Harold Kaese wrote in

mid-September. While the Sox played the

A’s on the last day of the season, Grove was honored between games of a

doubleheader. “Well, he’s a better guy

now,” said an unnamed Athletic. “All he

used to have was a fastball and a mean disposition.” Connie Mack said, “I took more from Grove

than I would from any man living. He

said things and did things – but he’s changed.

I’ve seen it year by year by year.

He’s got to be a great fellow.”

Grove quietly told owner Yawkey that he was retiring while

they walked through Yawkey’s hunting preserve in South Carolina in early

December. The news was upstaged by the

bombing of Pearl Harbor. Though he

suffered reverses in retirement that would have soured many – getting divorced,

outliving his only son, needing financial help from baseball – Grove nurtured

the kinder, gentler side of his character long suppressed. He outfitted Philadelphia sandlotters, sent

two youngsters through college, and coached kid teams around Lonaconing. He was chosen to the Hall of Fame in 1947,

his first year of eligibility.

Grove was a boisterous presence in his appearances at

Cooperstown. “When he saw the other old

players, like Joe Cronin, he would just haul off and sock them,” says Grove’s

friend David Schild. “If he considered

you a friend, he would punch you in the stomach or slap you on the back. If he really liked you, he’d hit you both

ways.”

After his ex-wife Ethel died in 1960, Grove moved to

his daughter-in-law’s home in Norwalk, Ohio.

He died there on May 22, 1975, at the age of 75. He is buried at Frostburg Memorial Park in

Frostburg, MD about nine miles from his hometown.

Sources:Kaplan, Jim. Lefty Grove: American Original by Jim Kaplan (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2000).

1.

www.baseball-almanac.com 2.

www.retrosheet.org 3.

www.baseballlibrary.com Full Name: Robert Moses Grove

Born: March 6, 1900, at Lonaconing, MD (USA).

Died: May 22, 1975, at Norwalk, OH (USA).