Former Names

1. Louisiana Superdome (1975 – 2011)

2. Mercedes-Benz Superdome (2011 – 2021)

Address: 1500 Sugar Bowl Drive

Location: New Orleans, Louisiana

Owner: The Louisiana Stadium and Exposition District

Operator: ASM Global

Capacity: 1. American Football: 73,208

(expandable to 76,468)(1)

2. Basketball: 73,432

3. Baseball: 76,468

Record Attendance: 78,133 (WrestleMania 34,

April 8th, 2018)

Surface:

1. Monsanto “Mardi Grass” turf (1975 – 2003)(2)

2. Field Turf (2003 – 2006)

3. Sportexe Momentum Turf (2006 – 2009)

4. UBU Speed Series S5 (2010 – 2016)

5. Act Global: UBU Speed S5-M Synthetic Turf

(2017 – 2018)

6. Turf Nation S5 (2019 – Present)

Construction:

Broke Ground: August 12th, 1971

Opened: August 3rd, 1975

Reopened: September 25th, 2006

Construction Cost: US$134 million (initial)

($759 million in 2023 dollars(3))

Renovations: US$ 193 million (2005 – 06 repairs)

($292 million in 2023 dollars(3))

Architect:1. Curtis and Davis Associated(4)

2. Edward B. Silverstien & Associates(4)

3. Nolan, Norman & Nolan(4)

Tenants: 1. New Orleans Saints (NFL) 1975 – Present

2. Sugar Bowl (NCAA) 1975 – Present

3. Tulane Green Wave (NCAA) 1975 – 2013

4. New Orleans Jazz (NBA) 1975 – 1979

5. New Orleans Pelicans (AA) 1977

6. New Orleans Breakers (USFL) 1984

7. New Orleans Night (AFL) 1991 – 1992

8. New Orleans Bowl (NCAA) 2001 – Present

9. New Orleans VooDoo (AFL) 2013

Designated on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places on January 27th, 2016(5)

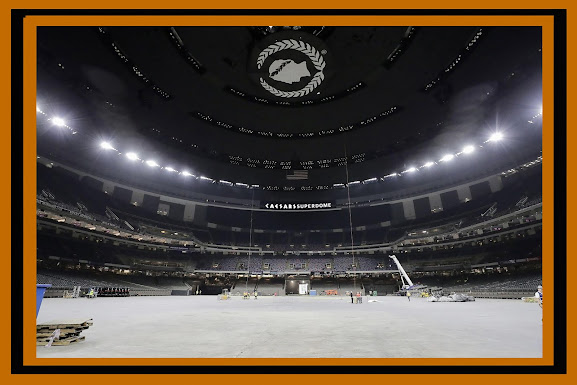

The Caesars Superdome (originally Louisiana Superdome and formerly Mercedes-Benz Superdome), commonly known as the Superdome, is a domed multi-purpose stadium located in the Central Business District of New Orleans, Louisiana. It is the home of the New Orleans Saints of the NFL.

Plans to build the Superdome were drawn up in 1967 by the New Orleans modernist architectural firm of Curtis and Davis and the building opened as the Louisiana Superdome in 1975. Its steel frame covers a 13-acre expanse and the 273-foot dome is made of a lamellar multi-ringed frame and has a diameter of 680 feet, making it the largest fixed domed structure in the world.(6)

The Superdome has routinely hosted major sporting events; it has hosted seven Super Bowl games (and will host its eighth, Super Bowl LIX in 2025), and five NCAA championships in men’s college basketball, the Sugar Bowl has been played at the Superdome since 1975, which is one of the “New Year’s Six” bowl games of the College Football Playoff (CFP). It also traditionally hosts the Bayou Classic, a rivalry game played between the HBCU’s Southern University and Grambling State University. The Superdome was also the long-time home of the Tulane Green Wave football team of Tulane University until 2014 (when they returned on-campus at Yulzman Stadium), and was the home venue of the New Orleans Jazz of the National Basketball Association (NBA) from 1975 until 1979.

In 2005, the Superdome housed thousands of people seeking from Hurricane Katrina. The building suffered extensive damage as a result of the storm, and was closed for many months afterward. The building was fully refurbished and reopened in time for the Saints’ 2006 home opener on September 25th.

Some History

Planning

Local businessman David Dixon (who later founded the United States Football League in the 1980’s) conceived of the Superdome while attempting to convince the NFL to award a franchise to New Orleans. After hosting several exhibition games at Tulane Stadium during typical New Orleans summer thunderstorms, Dixon was told by NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle that the NFL would never expand into New Orleans without a domed stadium. Dixon then won the support of the governor of Louisiana, John McKeithen. When they toured the Astrodome in Houston, Texas in 1966, McKeithen was quoted as saying, “I want one of these, only bigger”, in reference to the Astrodome itself. Bonds were passed for construction of the Superdome on November 8th, 1966, seven days after commissioner Pete Rozelle awarded New Orleans the 25th professional football franchise.

The stadium was conceptualized to be a multifunctional stadium for football, baseball and basketball – with moveable field level stands that would be arranged specifically for each sport and areas with dirt (for the bases and pitchers’ mound) covered with metal plates on the stadium floor (they were covered by the artificial turf during football games) – and there are also meeting rooms that could be rented for many different purposes. Dixon imagined the possibilities of staging simultaneous high school football games side by side and suggested the synthetic be white(7). Blount International of Montgomery, Alabama was chosen to build the stadium.(8)

As the dome was being constructed, various individuals developed eccentric models of the structure: one was of sugar, another consisted of pennies. The so-called “penny model” traveled to Philadelphia Bicentennial ’76 exhibition New Orleanian Norman J. Keintz built the model with 2,697 pennies and donated it to the Superdome Board of Commissioners in April 1974.(9)

It was hoped the stadium would be ready in time for the 1972 NFL season, and the final cost of the facility would come in at $46 million. Instead, due to political delays,(10) construction did not start until August 11th, 1971, and was not finished until August 1975, seven months after Super Bowl IX was scheduled to be played in the stadium. Since the stadium was not finished for the Super Bowl, the game had to be moved to Tulane Stadium, and was played in cold and rainy conditions. Factoring in inflation, construction delays, and the increase in transportation costs caused by the 1973 oil crisis, the final price tag of the stadium skyrocketed to $165 million. Along with the state police, Elward Thomas Brady, Jr., a state representative from Terrebonne Parish and a New Orleans native, conducted an investigation into possible financial irregularities, but the Superdome went forward despite the obstacles.(11)

Early history (1975 – 2004) The New Orleans Saints opened the 1975 NFL season at the Superdome, losing 21 – 0 to the Cincinnati Bengals in the first regular-season game in the facility. Tulane Stadium, the original home of the Saints, was condemned for destruction on the day the Superdome opened.

The first Super Bowl played in the stadium was Super Bowl XII in January 1978, the first in prime time.(12)

The original artificial turf playing surface in the Superdome was produced and developed by Monsanto (which made the first artificial playing surface for sports, AstroTurf) specifically for the Superdome, was named “Mardi Grass”.(2)

The Superdome replaced the first generation “Mardi Grass” surface to the next-generation FieldTurf surface midway through the 2003 football season on November 16th.

Shelter of last resort during Hurricane Katrina

Photo Credit

The Superdome was used as a “shelter of last resort” for those in New Orleans unable to evacuate from Hurricane Katrina when it struck on August 29th, 2005. During the storm, a large section of the outer covering was peeled off by high winds. The photo of the damage, in which the concrete underneath was exposed, quickly became an iconic image of Hurricane Katrina. A few days later, the dome was closed until September 25th, 2006.

By August 31st, there had been three deaths in the Superdome two elderly medical patients and a man who is believed to have committed suicide by jumping from the upper-level seats. There were also unconfirmed reports of rape, vandalism, violent assaults, crack dealing/drug abuse, and gang activity inside the Superdome. After a National Guardsman was attacked and shot in the dark by an assailant, the National Guard used barbed wire barricades to separate themselves from the other people in the dome(13). On September 11th, New Orleans Police Superintendent Eddie Compass reported there were “no confirmed reports of any type of sexual assault.”(14)

United States Navy sniper Chris Kyle claimed that during the hurricane, he and another sniper climbed to the top of the dome and killed 30 armed looters during the chaos following the event. This claim has never been independently verified, and there is no evidence of dozens of people being slain by a sniper or gunman, with commentary noting that it would be unlikely that 30 people would have been killed without anyone noticing it or reporting it to the media or the police. Kyle’s story has been reported in a number of publications, including the New Yorker, with Kyle relating the story to the other military personnel.(15)(16)(17)

The Superdome cost $185 million to repair and refurbish. To repair the Superdome, FEMA put up $115 million,(18) the state spent $13 million, the Louisiana Stadium & Exposition District refinanced a bond package to secure $41 million and the NFL contributed $15 million.

After being damaged from the flooding disaster, a new Sportexe MomentumTurf surface was installed for the 2006 season.

During Super Bowl XL on February 5th, 2006, the NFL announced that the Saints would play their home opener on September 24th, 2006 in the Superdome against the Atlanta Falcons. The game was later moved to September 25th.

The reopening of the dome was celebrated with festivities including a free outdoor concert by the Goo Goo Dolls before fans were allowed in, a pre-game performance by U2 and Green Day performing a cover of the Skids’ “The Saints Are Coming”, and a coin toss conducted by then-President George W. Bush. In front of ESPN’s largest-ever audience at that time, the Saints won the game 23 – 3 with 70,003 in attendance, and went on to a successful season, reaching their first ever NFC Championship Game.

2008 – Present

Further Renovations In 2008, new windows were installed to bring natural light into the building. Later that year, the roof-facing of the Superdome was also remodeled, restoring the roof with a solid white hue. Between 2009 and 2010, the entire outer layer of the stadium, more than 400,000 (37,000 m2) of aluminum siding, was replaced with new aluminum panels and insulation, returning the building to its original champagne bronze colored exterior. An innovative barrier system for drainage was also added, allowing the dome to resemble its original façade.

In addition, escalators were added to the outside of the club rooms. Each suite includes modernized rooms with raised ceilings, leather sofas, and flat-screen TVs, as well as glass brushed aluminum and wood-grain furnishings. A new $600,000 point-of-sale system was also installed, allowing fans to purchase concessions with credit cards throughout the stadium for the first time.

During the summer of 2010, the Superdome installed 111,831 square feet (10,389 m2) of the UBU Speed S5-M synthetic turf system, an Act Global brand. In 2017 Act Global installed a new turf in time for the NFL season. For the 2018, 2019, and 2020 NFL seasons, Turf Nation Inc. located in Dalton, Georgia, have supplied the synthetic turf system for the Superdome. The Superdome has, as of 2017, the largest continuous synthetic turf system in the NFL.

Beginning in 2011, demolition and new construction began to the lower bowl of the stadium, reconfiguring it to increase seating by 3,500, widening the plaza concourse, building two bunker club lounges and adding additional concession stands. Crews tore down the temporary stairs that led from Champions Square to the Dome, and replaced them with permanent steps. Installation of express elevators that take coaches and media from the ground level of the stadium to the press box were also completed. New 7,500-square-foot bunker lounges on each side of the stadium were built. The lounges are equipped with flat-screen TVs, granite counter tops and full-service bars. These state-of-the-art lounges can serve 4,500 fans, whose old plaza seats were upgraded to premium tickets, giving those fans leather chairs with cup holders. The plaza level was extended, closing in space between the concourse and plaza seating, adding new restrooms and concession areas. The renovations also ended the stadium’s ability to convert to a baseball configuration(19). The renovations were completed in late June 2011 in time for the Essence Music Festival.

Naming Rights Naming rights to the Superdome were sold for the first time in 2011 to automaker Mercedes-Benz, renaming the facility Mercedes-Benz Superdome(20). Mercedes-Benz did not renew the contract,(21) and in July 2021 it was announced that the naming rights would be sold to Caesars Entertainment, under which it was renamed Caesars Superdome.(22)(23)(24)

Statue On July 27th, 2012, a statue was unveiled at a plaza next to the Superdome. The work, titled Rebirth, depicts one of the most famous players in Saints history – Steve Gleason’s block of a Michael Koenen punt that the Saints recovered for a touchdown early in the first quarter of the team’s first post-Katrina game in the Superdome.(25)

Super Bowl XLVII power failure The Superdome hosted Super Bowl XLVII on February 3rd, 2013. A partial power failure halted game play for about 34 minutes in the third quarter between the Baltimore Ravens and the San Francisco 49ers. It caused CBS, who was broadcasting the game to lose some of its cameras as well as voiceovers by commentators Jim Nantz and Phil Simms. At no point did the game go off the air, though the game had no audio for about two minutes. While the lights were coming back on, sideline reporter Steve Tasker reported on the outage as a breaking news situation until power was restored enough for play to continue.

On February 8th, 2013, it was reported that a relay device intended to prevent an electrical overload had caused the failure(26). The device was located in an electrical vault owned and operated by Entergy, the electrical utility for the New Orleans area. The vault is approximately one quarter mile away from the Superdome. A subsequent report from an independent auditor confirmed the relay device as the cause(27). The Superdome’s own power system was never compromised.

End zone scoreboards and new lighting

During the 2016 off-season, the smaller videoboards formerly located along the end zone walls above the upper seating bowl were replaced with two large Panasonic HD LED displays that stretch 330 feet wide and 35 feet high that are much easier to see throughout the bowl(28). Other upgrades included a complete upgrade to the Superdome’s interior floodlighting system to an efficient LED system with programmable coloring, light show effects, and instant on-off; in normal mode the stadium will have a more vibrant and naturally pleasing system resembling natural daylight.(29)(30)

Current renovations In November 2019, phase one plans were approved by the Louisiana Stadium and Exposition District, commonly known as the Superdome Commission, for a $450 million dollar renovation. The renovation, designed by Trahan Architects (founded by Victor F. “Trey” Trahan III, FAIA), will include atriums that will replace the ramp system, improved concourses, and field-level end zone boxes(31). The first phase of work began January 2020(32) and includes installing alternative exits and constructing a large kitchen and food-service area.

2021 roof fire On September 21st, 2021, thick black smoke was seen rising from the top of the Superdome while renovations and maintenance were underway by workers on the roof. One person was injured in the blaze that initially started when a pressure washer caught fire. Firefighters brought the fire under control within an hour. No structural damage occurred to the building, and future events were not impacted.(33)

Links and References 1.

"The Superdome – An Icon Transformed" (PDF).

(PDF) on February 21, 2014. Retrieved

September 6, 2012.

Football.ballparks.com. Archived from

the December 14, 2011.

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Retrieved February 29, 2024.

(PDF). www.modernsteel.com. Archived from

December 14, 2011.

9. Louisiana Superdome Newsletter 5:7

Observer-Reporter. (Washington, Pennsylvania).

Associated Press. March 17, 1976. p. B6.

13. Scott, Nate (August 24, 2015).

"Refuge of last Nola.com. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

22. Around the NFL staff (July 26, 2021).

"Saints' NFL.com. NFL Enterprises, LLC. Retrieved

(Press release). NFL Enterprises, LLC.

July 26, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

24. McAuley, Anthony (July 26, 2021).

"Caesars, Associated Press. July 28, 2012. Retrieved

Associated Press. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

27. Thompson, Richard (March 22, 2013).

"Super Media Group. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

28. Duncan, Jeff (May 27, 2016).

"Massive new September 2, 2016.

29. Trahan, Sabrina (24 August 2016).

"Saints on 14 September 2016. Retrieved

September 2, 2016.

30. Ames, Don (August 26, 2016).

"Superdome September 19, 2016. Retrieved September 2,

2016.

31. McAuley, Anthony (November 14, 2019).

The Advocate Nola.com. Retrieved

February 11, 2020.

32. Adelson, Jeff (January 14, 2020).

"National The Advocate Nola.com. Retrieved February

11, 2020.

33. Daley, Ken (September 21, 2021).

"WATCH: